Elizabeth "Bessie" Williamson started her career at Laphroaig Distillery as a temporary secretary, and in the span of only four years she worked her way up to distillery manager.

The names of whiskey’s founding fathers could double as a dedicated drinker’s favorite bar order: George T. Stagg, Jim Beam, Jack Daniel,—and even ol’ Julian “Pappy” Van Winkle himself can be found on the shelves of the world’s best watering holes. But the women who shaped the history of bourbon, scotch, Irish, and Japanese whisky remain largely unknown to even the most sophisticated collectors.

And yet, without Nettie Harbinson, The Macallan would not be celebrating its 200th anniversary this year. Without Margaret Samuels, Maker’s Mark bottles would not have been hand-dipped in its now-iconic red wax had she not experimented with it at her kitchen table. And where would the entire Japanese whisky industry be without Rita Taketsuru (née Jessie Roberta Cowan), the Scottish-born woman who helped her husband finance his dream to build Nikka Distillery in Hokkaido?

Whisky lovers would do well to consider the women whose innovation, creativity, and fortitude built some of the world’s most acclaimed whiskies.

Ethel Greig Robertson, Edrington

Along with her two older sisters Elspeth and Agnes, Ethel Greig Robertson—affectionately known as Miss Babs—inherited her father James Robertson’s considerable estate in 1944: the Clyde Bonding Company and Glasgow-based firm Robertson & Baxter, an established broker and blender of scotch whiskies. While the sisters were united in their vision for their father’s estate, it was Ethel who oversaw the business affairs, thwarting aggressive takeover offers from rivals like whisky titan Samuel Bronfman of Seagram by combining their capital under a holding company called Edrington—named after one of the sisters’ Berwickshire farms. At the same time, they transferred the entirety of their shares to establish what is now Scotland’s largest independent charitable trust, which is Edrington’s sole shareholder: The Robertson Trust. Today, the trust distributes approximately £20 million ($25 million) across 500 charities each year.

Helen and Elizabeth Cumming, Cardhu

At the heart of Johnnie Walker are the “four pillar” distilleries, so called because they’re meant to represent the four corners of scotch whisky: Caol Ila (Islay), Clynelish (Highlands), Glenkinchie (Lowlands), and Cardhu (Speyside). Cardhu in Archiestown—then known as Cardow until a name change in 1981—was arguably the most important of them all, despite its initially unlawful status as it dodged the tax laws. During those days in the early 1800s, Helen Cumming, who helped run the place with her husband John, would camouflage the distillery as a bakery and invite tax collectors into her home for a meal—all while discreetly hoisting up a red flag to warn other distillers that excise men were in town. By 1824, when tax laws were finally eased, the distillery was legally registered and was eventually run with just two employees and Cumming’s son Lewis. But upon Lewis’s death, Helen urged her daughter-in-law Elizabeth to take over. Under Elizabeth, the distillery saw massive expansion in 1884, gaining four acres of land and new equipment to increase production capacity. Within 10 short years, production tripled. And by 1893, Elizabeth sold the distillery to John Walker & Sons Limited, cementing her status as one of the great women in whisky history.

Rita Taketsuru, Nikka Whisky

Considered the Mother of Japanese whisky, Scotland-born Rita Taketsuru (née Cowan) fell in love with a lodger in her mother’s Kirkintilloch home: Japanese chemist Masataka Taketsuru, who hailed from a long and wealthy line of sake brewers. Masataka, who dreamt of “making real whisky in Japan” married Rita and apprenticed in Campbelltown before moving to Japan, spending 10 years outside Osaka overseeing the construction of what is now Suntory Yamazaki Distillery. Eventually, the couple settled down in Yoichi, a small town in Japan’s northern island of Hokkaido, which they believed to be climatically similar to Speyside. There they began to pursue their dreams of building their own distillery—with Rita providing moral and financial support from her income as an English teacher, in addition to building a vast network of potential investors. Today, the company has expanded exponentially, thanks to the Taketsurus’s adopted son Takeshi—so much so that it now owns Yoichi and Miyagikyo distilleries in Japan as well as the Ben Nevis Distillery in Fort William, Scotland. Archives related to Rita and Masataka’s story can be found at the Auld Kirk Museum in Kirkintilloch.

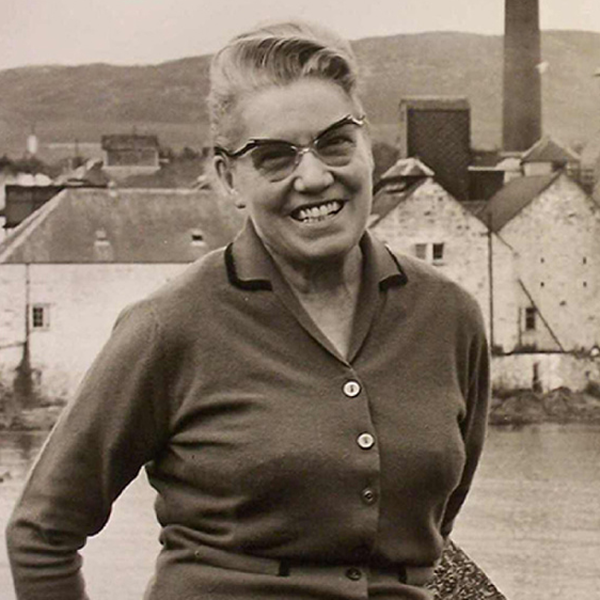

Bessie Williamson, Laphroaig

Shortly after World War II, Laphroaig was in crisis—as were many other scotch distilleries—having had to cease production and divert their stores of grain to provide sustenance to soldiers. But under the leadership of Elizabeth “Bessie” Williamson, a Glaswegian who moved to Islay in 1934—working her way up from temporary secretary to distillery manager in just four years as owner Ian Hunter’s righthand woman—Laphroaig began to thrive. It was during these post-war years that Williamson made the bold decision to promote Laphroaig as a single malt while also overseeing its expansion and acquisition by Long John International (then known as Seager Evans). “She earned respect from understanding the business—literally from the ground up,” says Simon Brooking, senior ambassador of Scotch heritage at Beam Suntory, Laphroaig’s parent company. “She understood what was needed to run a tight ship financially, but also took care of the workers…she was very magnanimous.” Outside of her work in the whisky industry, Williamson was also popular among Islay’s residents for her contribution to the island’s social endeavors, organizing celebrations and concerts for local charitable causes—and in 1963 she was awarded the Order of St. John for her kind deeds.

Margaret “Margie” Samuels, Maker’s Mark

A chemist by training, Margaret “Margie” Samuels, was the creative force behind the branding of her husband Bill Samuels Sr.’s whiskey—Maker’s Mark: She hand-dipped red wax seal and hand-cut its label (which, unlike most bourbon brands at the time, did not bear a family name). “She had exquisite taste and before bourbon tourism existed, she transformed Star Hill Farm—the Loretto, Kentucky distillery and she was the one who said, ‘Let’s design the place to balance function and form and make it welcoming; make it personal,’” recalls her grandson and chief operating officer of Maker’s Mark Rob Samuels. “They didn’t like traditional marketing. They thought it was rude. You know, screaming the loudest to connect with the customer…she believed in branding that didn’t feel like marketing.” In 2014, Samuels became the first woman to be inducted into the Bourbon Hall of Fame for her considerable contributions to a distillery.

Janet Isabella Harbinson, The Macallan

The first female managing director of The Macallan, Janet Isabella “Nettie” Harbinson, was the daughter of Roderick Kemp—the distillery’s owner from 1892 to 1909. Upon his death, the business was taken over by her husband, Dr. Alexander Harbinson, who died nine years later—leaving Nettie the difficult decision of whether to assume control of The Macallan or to put it up for sale, amid pressure from stakeholders. She chose to run the distillery, not only as a way to preserve her family legacy but to also secure the futures of her employees, whom she very much cared for. She also is the woman behind The Macallan Valerio Adami Fine & Rare 1926—which became the world’s most valuable whisky when it sold for $2.7 million at Sotheby’s in November 2023.

Augusta Dickel, George Dickel

In 1888, George A. Dickel was disabled due to injuries sustained from falling off a horse. It was a turning point in the Tennessee distillery’s history, which was then known as Cascade Hollow. Following the accident, Dickel’s wife Augusta stepped up and took over many of his responsibilities, working hand-in-hand with Victor Shwab—her brother-in-law and one of George’s most trusted employees. Six years later, in the summer of 1894, George died and left his share of the company to Augusta with strict instructions to sell “at the first favorable opportunity.” Without paying much mind to George’s final wishes, Augusta kept the distillery in the family and traveled throughout Europe with whiskey in hand intending to spread the word about Dickel whiskey—while Shwab took care of the day-to-day operations. Augusta and Shwab also furthered their business interests by investing in downtown Nashville real estate. By the time Augusta died in 1916, having no children of her own, she left her sizeable fortune of $1 million—around $29.7 million in today’s dollars—and her share of the business to Shwab.