Dublin-based Teeling Distillery brought single pot still whiskey back to Ireland's capital city after it nearly vanished in the 20th century. Master distiller Alex Chasko pictured.

For many years after the near-collapse of the Irish whiskey industry in the 1960s and ’70s, innovative whiskey making in Ireland was nearly extinct. That dearth of artistry was by necessity, as all efforts were centered on just a handful of brands in order to get Irish whiskey back on its feet again. The wilderness years lasted nearly three decades, but Irish whiskey creativity has finally returned to the fore, with innovators tapping into terroir, creating modern twists on Irish whiskey’s past, and pushing the envelope on flavor. Here’s a look at what’s happening.

Boann Distillery

Salvaging History in a Dram

Boann Distillery started making whiskey in 2019, and is using the past to inspire the future. Soon after opening, Boann partnered with Irish whiskey historian and author Fionnán O’Connor on its vintage mashbills project to test 10 historic recipes. Since then it has been on a mission to be one of the more creative players in the Irish renaissance.

The Boann vintage mashbills project has explored the use of adjunct grains—oats, rye, and wheat. But it’s far more complicated than just adding other cereals; what’s removed is equally important. The secret is to maintain 10% more barley than malt to ensure the pot still oils remain. Oats add an artificial sweetness—cotton candy and Pop Rocks, wheat serves up pastry and notes of buttered bread with a hint of musty hay sheds, while a higher malt-to-barley ratio delivers plum and jammy notes.

At first glance, the distillery, located a short drive north of Dublin, appears simply to be a traditional Irish single pot still and single malt maker. But a look inside reveals a veritable laboratory, packed with gadgetry and technical wizardry to help drive innovation. Among many unusual items is the nano-structured copper surface inside the necks of the Italian- built stills. The interior is coarse and uneven, like sandpaper, producing a six-fold increase in surface area to better purify the spirit vapors. There’s a reflux coil in the still’s neck that can be turned on, off, or partially on, to allow cool water to vary the degree of reflux. The condensers are built in reverse, so that vapors, not cooling liquid, pass through the tubes, further deepening that copper conversation, and there are sub-coolers too, to chill down the distillate to even colder temperatures, trapping more volatiles.

Boann is now using 35 mashbills and three different distillation methods. Master distiller Michael Walsh has filled 50 different types of casks, opening up almost limitless possibilities for future recipes. Boann is thus building an enormous flavor library of whiskeys, and this endeavor appears set to play an important part in the next phase of Irish whiskey’s restoration.

The Busker

Tapping the Sweetness of Marsala Casks

The Busker is made at Royal Oak Distillery, established in 2013 and located about 60 miles south of Dublin. It’s owned by Italy’s Illva Saronno Holdings, which is best known for its Disaronno amaretto liqueur. This was the home of Walsh Whiskey until 2019, when it dissolved its partnership with Disaronno in a deal that left Disaronno with full ownership of the distillery and Walsh becoming a non-distiller producer retaining ownership of its Writers’ Tears and The Irishman brands.

Today, Royal Oak’s focus is on people who find whiskey intimidating. The Busker blend is rounded and easy to drink, not aiming for the complexity that would appeal to more seasoned Irish whiskey drinkers. It has a conspicuously contemporary look so as not to appear like a stereotypical Irish whiskey or intimidate new drinkers by appearing too expensive or too complex.

The distilling team, led by former Diageo master blender Caroline Martin, is able to work with a ready supply of marsala casks from the Illva Saronno estates in Sicily. In addition to its blend, The Busker’s range includes a single malt aged in sherry and bourbon casks, a single pot still, and a single grain expression aged in bourbon and marsala casks.

Midleton Distillery

Returning to Irish Oak

When Midleton Distillery master cooper Ger Buckley made a small tub from Irish oak in 2007, it was the first piece of Irish oak coopering in over 100 years. Eight years later in 2015, the idea of finishing single pot still whiskey in new Irish oak was realized with the debut of Midleton Very Rare Dair Ghaelach.

Buckley and Midleton master distiller Kevin O’Gorman (who was master of maturation at the time) came up with the idea of tracing each whiskey back to its individual tree after watching 170–180 year old Irish oaks being felled for the project in Grinsell’s Wood, County Kilkenny. Buckley traveled to Galicia in northern Spain, where the logs were quarter-sawn at the Maderbar sawmill in Baralla before driving south to Jerez, where the staves were air-dried for 15 months at the Antonio Paez Lobato cooperage. Once the oak was seasoned, Spanish coopers made hogsheads from the wood. The team, led by O’Gorman and master blender Billy Leighton, chose 15–22 year old single pot still whiskey for this project because it was robust enough to stand up to new Irish oak. “You don’t put a lightweight up against a heavyweight,” explained O’Gorman.

The fourth and most recent release in this series, Kylebeg Wood, includes 15-28 year old single pot still whiskeys and was the first project to involve blender Deirdre O’Carroll. “We sampled these casks every month, which is frequent given the age of the liquid inside,” says O’Carroll, who noted the variations in color and flavor between individual casks. “That’s the essence of a single cask, just how different everything can be, when on paper they can be the same.” The blending team made a composite sample for each tree and then nosed it against the original whiskey.

“After 15 months, we got a balance of spicy, robust pot still coming through, but with lovely sweet nuances from the Irish oak cask,” says O’Carroll. There were variations between individual trees too, with certain ones producing sweeter or spicier variants. “It’s a blender’s dream to have the same liquid going into each cask and be able to taste these differences,” she adds.

The Method And Madness Japanese trilogy is another example of Midleton’s creativity in working with wood. The whiskeys are finished in three different types of Japanese wood: mizunara, cedarwood sourced from a Japanese cooperage that makes cedarwood casks for sake, and chestnut casks made for shochu. Japanese chestnut, Castanea crenata, produces licorice and menthol notes in whiskey. The mizunara cask was filled with a 30 year old single pot still whiskey and left for another 3 years. There was lots of spirit loss, due to the porous nature of mizunara. “When you finally empty that barrel and see how much you’ve lost, it’s heartbreaking,” says master of maturation Finbarr Curran. But he hopes the results make it all worthwhile.

Powerscourt

Creative Mashbills and New Flavors

Powerscourt Distillery is located just south of Dublin on the Powerscourt Estate House & Gardens in County Wicklow, a property that boasts two championship golf courses, a hotel, and Ireland’s highest waterfall. The distillery’s flagship label is Fercullen, with Fercullen Falls and Fercullen single malt made using single malt whiskey distilled on the estate. Fercullen Falls is a blend with 50% malt in the mashbill. It’s bottled at 43% to help it stand up in long drinks, cocktails, and Highballs.

The Powerscourt team, led by distillery manager Paul Corbett, formerly of Clonakilty, does five mashes a week, keeping a production schedule of 250,000 liters of pure alcohol annually, split 75:25 between single malt and pot still whiskeys. Corbett describes the aromas of the sweet Powerscourt new make as being similar to opening a bag of marshmallows. He’s pushing the boundaries of single pot still production, planning a porter-style mashbill using 6.5% chocolate malt and 3.5% oats, followed by a crystal malt mashbill that should bring out pizza crust flavors, with the oats adding sweetness, body, and enhancing the mouthfeel.

The Powerscourt estate grows 100 tons of barley annually, which is used as the unmalted element in its single pot still whiskeys. Typically, a 60:40 ratio of malted to raw barley is used, but Corbett has also tried flipping it to make a heavier, oilier pot still batch that’s less sweet and considerably spicier. There are plans for experimental single malts too, with batches made from amber malt—a slightly more kilned malt that delivers tasty caramel flavors—and hefeweizen yeast, an ale yeast that can deliver banana and tropical fruit flavors.

The Shed

Singular Focus on Traditional Pot Still

Located in the picturesque village of Drumshanbo in north-central Ireland, The Shed Distillery is a remote and scenic outpost that’s well worth the trip. Owned by drinks industry veteran P.J. Rigney, The Shed opened in 2014 and initially became known for its Gunpowder Irish gin label. But the distillery was also laying down whiskey from the start, focusing exclusively on single pot still. Five years later, in December 2019, The Shed launched its first Irish whiskey. The five-year wait was deemed the proper amount of time to get the single pot still style right, in the view of both Rigney and master distiller Brian Taft, and Drumshanbo has stuck with that maturation policy.

The distillery tour takes you on the curious journey of The Shed’s origin story, where you can see the Holstein stills where Taft produces triple-distilled Drumshanbo single pot still whiskey using traditional methods from malted and unmalted barley and a small amount of oats, and its vodka and Gunpowder gin. The Shed also has a top-flight café among its visitor amenities.

Teeling

Reviving Single Pot Still Whiskey in Dublin

Dublin’s pot still whiskey production nearly vanished in the 20th century, as Jameson, Powers, and the Spot whiskeys decamped in the depressed 1970s, merging and reconstituting to the west as Irish Distillers in Midleton, County Cork. Dublin-based Teeling Distillery rose from the ruins of those great legacies in 2015, marking the return of single pot still whiskey to the capital city.

Most whiskey drinkers only know the flavors of modern single pot still Irish whiskeys like Redbreast and Powers, all made at Midleton. In its early forays into reviving this genre, Teeling discovered that the bold flavors of the antique single pot still expressions had their own personas. It tracked down some antique Irish whiskeys, opening old Dublin-made bottles of mid-20th century Powers and Jameson. “Those pot stills tasted totally different from what’s being made today,” says Teeling master distiller Alex Chasko, “I don’t think people would like it.” Unlike Midleton’s 60:40 mashbill of barley and malt, Teeling chose a 50:50 ratio based on experience with small batches produced by the Teelings when their father John owned Kilbeggan Distillery.

After some early glitches, by 2018, Teeling had something for the home crowd to taste. “[Irish whiskey drinkers] may have wanted a knock-off of Redbreast, but that was the exact opposite of what we wanted to do,” says director of sales and marketing Stephen Teeling. “We’re trying to introduce something from a different world, and this is only the start.” Chasko notes that the initial releases leaned heavily into the spirit rather than the cask.

With its Wonders of Wood series first using virgin Chinkapin oak then virgin Portuguese oak, Teeling is starting to explore new flavors in single pot still from a cask perspective.

Walsh Whiskey

Reimagining the Golden Era of Irish Whiskey

Bernard Walsh knows the stories of old Ireland and the whiskeys his grandfather drank. “The blend of the day was pot and malt,” he says. “Ireland was famous for it; a big-bodied whiskey that was creamy, oily, and typically non-peated, which helped the distilleries to differentiate themselves from their neighbors across the sea.” Walsh’s The Irishman label is more malt-forward, while its Writers’ Tears favors pot still flavors. When he founded Walsh Whiskey in 1999, Walsh was permitted to label his blends as pot still Irish whiskey, reflecting the components’ shared distillation method, but then a new definition of single pot still whiskey was announced by the Irish Whiskey Association in 2014. Walsh’s distinctive pot and malt combination was swallowed under the broad definition of Irish blends. It has released single malt and blended whiskeys for 24 years without ever including grain whiskey.

“I’m infatuated by what was lost here in Ireland,” adds Walsh. “We’re rediscovering that history and trying to bring it to life, but we’re also trying to write the future of Irish whiskey. It’s no good just imitating something done in the past—it would be disrespectful to not pursue a level of improvement.”

Waterford Distillery

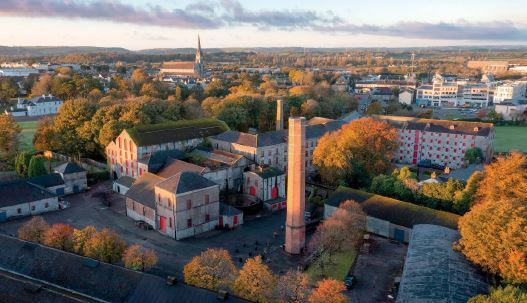

Irish Terroir At The Center

Since 2015, Waterford Distillery’s focus on barley and terroir has been relentless. Its complex program of single farm-origin whiskeys, heritage grain projects, and organic and biodynamic single malts means the distillery works with 500-1,000 different Irish farms. Waterford also employs a terroir specialist—Angelita Hynes, who coordinates all terroir projects with the production team and its partners in agriculture and academia. The distillery prints a téireoir code on its labels that links to a web page on the making of its whiskey—complete with sound clips, details on soil type, harvest dates, and farmers’ names. “I want people to see what we experience when we go to a farm,” Hynes says.

Having introduced single-farm origin and organic whiskeys, Waterford has also released a biodynamic whiskey made with barley that was planted, grown, and harvested in line with the lunar calendar. Next came peated Irish single malts. “Terroir isn’t just about the land,” argues Hynes. “It’s also about farming practices [and] the amount of sunlight and rain.”

Hynes is also involved in Waterford’s heritage grain project, searching for lost flavors of single malt Irish whiskey. Varieties such as Hunter (introduced in 1959), Goldthorpe (1889), and Old Irish, an indigenous barley variety that predates agricultural records, are all being grown. It has taken five years to grow enough barley to make the first batch, working with seed banks and seed breeders. Modern varieties may provide superior yield and disease resistance, but Hynes believes that could come at the expense of flavor, likening it to the uniformity of supermarket produce.

FARM DISTILLERS: Tapping into Ireland’s Terroir

Tipperary Boutique Distillery

Founded in 2014, this small farm distillery with big ambitions typifies such an endeavor. Scottish-born Jennifer Nickerson is the managing director, and her husband Liam Ahearn farms the land for the raw materials for their grain-to-glass production. Together with Jennifer’s father Stuart, a veteran scotch whisky distiller, Tipperary began distilling in 2020, while releasing sourced whiskeys and some editions made from barley on their own fields, distilled elsewhere but matured on the farm. Their grain-to-glass whiskeys from the farm should be rolling out of the warehouse next year.

Ballykeefe Distillery

The Ging family combines farming and distilling at Ballykeefe Distillery in the countryside near Kilkenny. Distilling 100% field-to-glass since 2017, Ballykeefe makes single pot still, single malt, and rye whiskeys.