Pat Fallon’s health was rapidly deteriorating when he reached out to Francisco Melendez in 2022.

The 52 year old former Marine was in full kidney failure following a series of medical misfortunes stemming from a lung injury. With dialysis as his lifeline, “The only solution was a new kidney,” Fallon recounts, “but no one I knew was a viable donor.” To amplify his plea, Fallon tapped Melendez, founder of a Texas nonprofit and The Sinner’s Club, a whiskey group on Facebook of which Fallon was a member.

Melendez raced into action, blasting Fallon’s dire situation to the entire 5,800-member group. Within minutes, a dozen offers to get tested flooded in; within weeks, five had completed the test. One, a bubbly coordinator for an audiologist and part-time bartender named Brittany McCaffety, was a perfect match. “I called Francisco and Pat and said ‘This is happening!’ and we all cried on the call,” McCaffety says.

After the June 2023 surgery, both are on the mend, and Fallon’s medical outlook appears supremely bright. Ask him if he expected his life to be saved by an online whiskey group, and his reply is swift: “Absolutely not. I underestimated that community at large.” Decrying Facebook as a black eye for the whiskey industry is easy; scoundrels, braggarts, and despicable deeds abound on the social platform’s bourbon groups, price-gouging on secondary boards, or worse—selling refilled bottles.

But the rotten apples aren’t spoiling the whole tree.

Heaps of goodwill and generosity still shine in many of the Facebook whisky groups. “I started New York City Bourbon Drinkers (NYCBD) to help people find good bourbon to drink locally,” says Andrew Castelli of the now 2,000-member page. Castelli initially wanted a cheaper marketing method for the very reasonably priced pours at his Harlem, New York bars, Uptown Bourbon and Penny Jo’s, an aim that was quickly embraced.

As NYCBD’s page exploded with proclamations of various stores or bars with good pricing, Castelli enlisted Shawn Kim, owner of 120 West 58th Street Wine and Liquor, for administrative help, Justin Cordova, a high school history teacher, and Tang Fan, a banker, also stepped into leadership roles, collectively setting the group’s bearing toward positivity.

“For example, there’s no price shaming,” details Castelli. “We shut that down real quick. If you want to do that, go to ‘Sketchy Liquor Stores,’” a national Facebook group dedicated to showcasing absurd bottle pricing. Initially, the group’s only membership requisite was to pledge not to be a jerk. “Bourbon groups can be filled with toxicity. We have a group text where if we see anyone being a jerk, we boot them immediately,” Fan says—though recent rules include no selling or flipping, and include instructions on how to trade bottles fairly.

NYCBD’s lack of vitriol is welcoming, particularly to Rachna Hukmani, a whiskey industry veteran of more than 15 years in a male-dominated field. “I’ve left other [Facebook] groups because there were no women, or if a woman says something, she’s ridiculed.” Hukmani notes there are other groups that are run by people who are discreetly supported by big brands. Honest conversations or polite discord aren’t welcome in those groups. “You can be booted for an opinion,” she says, because the administrators are in partnership with the brands.

Hukmani, who runs a sensory-focused immersive whiskey experience company called Whiskey Stories, believes NYCBD “is a safe space for everyone. We all love whiskey, regardless of gender. I can share my knowledge and expertise, and vice versa.”

Getting To Meet In-Person

As the group’s collective knowledge grew, so did their desire to meet one another, so Fan and Cordova organized bottle shares, sold-out affairs with more than 50 participants held at various New York venues owned by the group’s members, the members’ enthusiasm made evident by their bringing Pappy Van Winkles and dozens of other allocated unicorns.

Throughout the pandemic, Fan and Cordova leveraged the group to raise more than $15,000 for various charitable causes, including efforts against anti-Asian discrimination and to revive Chinatown. One fundraiser collected enough to purchase and deliver 120 meals to hospital workers during the height of COVID, Cordova says.

Though Cordova and Fan meet weekly for drams and to plan group initiatives, our interview is the first time the full quartet has physically met since the group’s launch in 2018. Here, in the cozy bar ambience of Castelli’s Penny Jo’s, their lively conversation evokes a family reunion feel—complete with razzing. This sense of camaraderie among strangers is the whole point, notes Kim. “You see long-term friendships springing up all the time; people going to each other’s houses, barbecues, and weddings,” Kim says. “Who’d think New York would have a community like this?”

Security Monitoring

Virtual communities that are focused on providing service and value also thrive, such as BSM Value Reference. This 35,000-member Facebook group, started by Kenny Levine and Pete Koma in 2019, exists as a historical database of bourbon’s secondary market pricing. “Come to the group, search any bottle you want and, if it’s been sold in the last seven years [on the secondary market], you can see the price and date of sale,” Levine says.

Pricing verification is conducted, particularly when members post erroneous numbers, by checking with secondary group admins. With several thousand bottles included, Levine often gets thank-you messages for the information. A typical scenario is when “someone died and left a bottle, and [the new owner] doesn’t know what it’s worth,” he says.

There’s even a page for the arbitration of soured secondary deals—both sales and trades—Bourbon’s Reasonable Magistrate (BRM). Watching cases and accusations fly around BRM’s “People’s Court,” as it’s known, is as entertaining as its namesake TV show. It’s a hub to warn others about blatant Facebook scammers, but also to air grievances arising from buying protocols and shipping logistics.

For example, if a bottle gets broken in transit, for any reason, the code of the secondary market is that the shipper bears the onus to rectify the issue—either with a refund or another bottle. Fail to comply, and the case ends up here, with scores of screenshots of private messages laid bare so the 22,000 members can dissect them in the comments, debating the case’s merits. Anonymous admins from the page sometimes issue verdicts, though repercussions are minimal; beyond banning the guilty party from all secondary groups, there’s little to enforce. An air of silliness envelops this group, although the shame from being called out—and the advocacy for the drinker—is palpable.

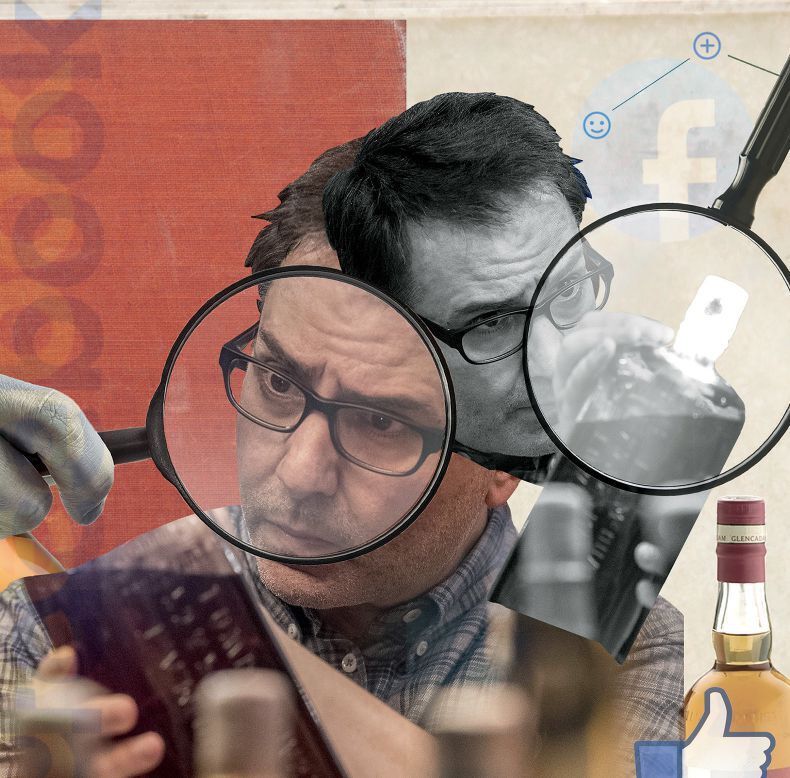

Adam Herz is a frequent poster within BRM People’s Court under his watchdog page, Herz’s Serious Whiskey Info. Herz, a Hollywood screenwriter and founder of Los Angeles’s Whiskey Society, meticulously investigates then traps counterfeiters, cornering them into direct message confessions like a Chris Hansen of whiskey. He curates and contextualizes the takedowns in an engaging series of screenshots and other media. He’s outed dozens of fraudsters, cultivating a sizable following of 7,800 fans.

While he notes that Facebook has plenty of problems—“You get idiots looking for attention there.”—Herz has also seen “massive amounts of cooperation and people helping one another.” And he understands Facebook is the easiest way to reach a mass audience with information about counterfeit whiskey. “People pass along tips that often bear fruit,” Herz says. And, through the platform, volunteers with special investigative skills or access have emerged, enabling Herz to cast a wider net and ensnare more ne’er-do-wells.

Anything Is Possible

In some groups, random acts of kindness snowball wonderfully. Inane trade requests occasionally escalate into wild results. “One guy started with a bottle of Old Grand-Dad, looking to trade his way to a Michter’s 20 year old,” recalls Joey Smith (not his real last name) an Illinois physician who’s active in several bourbon groups. “But we’re all rooting for him, watching him climb that mountain, wondering if he’ll get there. Everyone gave a little bit and he did it; he got the Michter’s.” (Smith also remembers another fellow who traded a bottle of Mellow Corn up, incredibly, to a Pappy Van Winkle.)

When a whiskey group mobilizes, anything becomes possible. Fan remembers during one of the NYCBD’s bottle shares, “Someone mentioned Travel Bar, owned by one of the group’s members, was in the running for this Bibber Cup contest for New York’s best whiskey bar, but was a few votes shy,” Fan says. “All 40 of us at the bottle share immediately voted and pushed it to a victory.”

Mike Vacheresse, co-owner and beverage director of Travel Bar in Brooklyn, was moved, and saw a nice uptick in business. “NYCBD is like an advice column by 2,000 people you can trust,” he says. “A lot of people come in from the group because they know we’re incredibly priced and have a well-curated list. They’re seeking to try an ounce of a whiskey they have at home; they’re not sure whether they want to sell it or open it.”

When business meets enthusiasts, business usually sees profit. Accordingly, Kim saw a 100% rise in bourbon sales after becoming active in NYCBD. “I would do about 30 barrel picks per year, and half of those sold out solely because of the group,” he says. But Kim also pays it forward, via raffles for Buffalo Trace Antique Collection products at MSRP, or surprise “equal sales,” where the likes of Rock Hill Farms or Jack Daniel’s Single Barrel are affordably priced, as long as you buy something equally priced or higher. Kim also frequently broadcasts distributor information, such as when awaited releases are hitting stores, enabling members who like to hunt to get moving.

In some groups, random acts of kindness snowball wonderfully.

Stewardship of the overwhelming majority of this benevolence comes without financial gain, and with a multitude of dedicated hours. Cordova spends “easily an hour a day” on the group, Fan spends five or more hours a week, and Herz carves out hours from his regular work schedule to dive into a “pile of waiting tips.”

Melendez says he “didn’t sleep for three weeks” working to raise money for Fallon and McCaffety. “Brittany was working two jobs, so I told her ‘I’ll get your bills covered,’” he says. Through raffling off 50 or so bottles, Melendez secured more than $30,000 for McCaffety’s expenses. “We hustled, but we got there.”

For Melendez, who works as an armed bodyguard for high-profile individuals, assisting others is simply a way of life. He’s decamped to several natural disasters, volunteering for relief efforts. In Houston, after Hurricane Harvey, he helped rescue six police officers from drowning in a river, receiving accolades from the governor and the president. His Melendez Foundation funds many philanthropic activities, including a battered women’s shelter in Colorado, or donating to the families of servicemen killed in a Blackhawk helicopter crash in Kentucky.

Melendez came to appreciate whiskey after “tasting all the high-end bottles my clients would offer,” refining his palate enough to become a solid barrel picker. Working with the likes of Copper Sky Distillery and J. Mattingly, among others, Melendez gifts his picked bottles to individuals who donate to his foundation. “Each barrel is usually aligned with a specific cause,” he notes. When the call went out for Fallon’s kidney search, he told the group, “If anyone wants to step up and get tested, you’ll get a lifetime supply of whiskey.”

One Good Deed a Day

But free whiskey wasn’t the driving force for McCaffety’s altruism. “Like Pat, my grandfather was a Marine, and he instilled [in me] that I should do one good deed a day, big or small,” she says. “My good deed that week was getting tested.” And when told she was a match, “I didn’t think twice about doing it,” she recounts.

McCaffety never met Fallon, not even during the year of testing before the surgery. But her conviction to this monumental endeavor never wavered, and it actually grew. “Anytime I would ask Pat if he was excited, he’d say, ‘You know how you get excited at Christmas and then you get a pair of socks? I’ll get excited when we’re wheeled back for surgery because then I’ll know it’s real.’ So I had socks made with my face on them and the green ribbon that symbolizes organ donation.” She gifted Fallon his pair the day before the surgery, when they finally met after a final round of testing. “I’m wearing them right now,” Fallon beams during our video interview, drawing a huge grin from McCaffety. (McCaffety also had T-shirts made that say “Kidney Buddies for Life,” which the duo wore during pre-op testing.)

“We’ve never even drank together,” Fallon admits. When cleared by the doctors, “I have a 2015 E.H. Taylor Barrel Proof that I’ve been waiting to crack.” McCaffety can’t wait for that moment: “Oh, hell yeah! I’m ready to celebrate with you.”